- Educator’s Classroom Guide

- Discussion Guide for Adult Learners

- Discussion Guide for Parents and Caregivers

- Learn more at The News Literacy Project

“Flopping Frogs,” about the evolution of the tailed frog, is one of the articles I sold to Highlights for Children. I also developed language arts resources to complement the piece.

“Flopping Frogs,” about the evolution of the tailed frog, is one of the articles I sold to Highlights for Children. I also developed language arts resources to complement the piece.

I developed all of the educator guides for this kit. From the publisher: “This kit helps to build social studies content-area literacy by integrating dynamic primary sources into the classroom! This comprehensive kit uses original documents, maps, photographs, and other materials to engage students in learning the history of California.”

I developed all of the educator guides for this kit. From the publisher: “This kit helps to build social studies content-area literacy by integrating dynamic primary sources into the classroom! This comprehensive kit uses original documents, maps, photographs, and other materials to engage students in learning the history of California.”

Best friends Rosemary Bennett and Adam Steiner find an old book that belonged to local poet Constance Brooke in Rosemary’s house. When words mysteriously appear in the book and the pair discover a magic spell, Rosemary and Adam accidentally make Adam’s sister, Shelby, disappear into a void. They follow clues through Shakespeare’s works and Constance Brooke’s Alzheimer’s to reverse the spell. Battling time, forces of nature, and their own forgetting, Rosemary and Shelby race to bring Shelby back before she is lost forever.

Best friends Rosemary Bennett and Adam Steiner find an old book that belonged to local poet Constance Brooke in Rosemary’s house. When words mysteriously appear in the book and the pair discover a magic spell, Rosemary and Adam accidentally make Adam’s sister, Shelby, disappear into a void. They follow clues through Shakespeare’s works and Constance Brooke’s Alzheimer’s to reverse the spell. Battling time, forces of nature, and their own forgetting, Rosemary and Shelby race to bring Shelby back before she is lost forever.

Themes of memory, belief in magic, overcoming loss and abandonment, and the power of literature pervade this book. View the teachers’ guide.

I’m thrilled share two educators’ guides for This is Not a Normal Animal Book, written by Julie Segal-Walters and illustrated by Brian Biggs.

This is Not a Normal Animal Book begins as a stroll through common, everyday, normal animals – mammal, bird, amphibian, insect, reptile, and fish. The story quickly evolves, however, into a meta-fiction disagreement between the author and illustrator over how to draw the animals. The author wants simple, normal animal drawings. The illustrator, however, is confused and makes a bit of a mess. From a cat, to a hen, to a frog, to a bee, to a snake, the illustrator grows increasingly frustrated over how the author wants each animal presented. The conflict reaches its peak when the illustrator refuses to draw the author’s choice of fish. Granted, the blobfish is an unusual choice of fish. The illustrator’s sense of humor and author’s deadpan seriousness come full circle in the closing line, when the author continues to frustrate the illustrator until the very end, and the illustrator continues to have the last word.

Based on a Yiddish proverb, the book is a behind-the-scenes look at the picture book creation process, the importance of collaboration and compromise, and the beauty of both words and art. This is Not a Normal Animal Book is a commercial story that breaks the fourth wall, while still remaining appropriate for classroom use. In addition to the themes and concepts mentioned, it also highlights the literary device metafiction and includes nonfiction back matter.

Click here to download the guide for Pre-K through Grade 2, and here to download the guide for Grades 3-6.

Teacher friends, if you’ve been overwhelmed by sorting through the amount of information online or have grown frustrated when trying to assess the authenticity of an article, you might be interested in my latest project for Teacher Created Materials. It’s called Information Literacy: Separating Fact from Fiction. In ten chapters, Sara Armstrong and I talk about finding, analyzing, and using information in today’s world. This deals with oldies but goodies like how to use graphic organizers and primary sources, and it incorporates new material such as how to spot fake news and online search tips to save you a googol of time. For educators who wish to blog and produce resources outside of the classroom, it also includes a chapter on copyright and fair use.

Teacher friends, if you’ve been overwhelmed by sorting through the amount of information online or have grown frustrated when trying to assess the authenticity of an article, you might be interested in my latest project for Teacher Created Materials. It’s called Information Literacy: Separating Fact from Fiction. In ten chapters, Sara Armstrong and I talk about finding, analyzing, and using information in today’s world. This deals with oldies but goodies like how to use graphic organizers and primary sources, and it incorporates new material such as how to spot fake news and online search tips to save you a googol of time. For educators who wish to blog and produce resources outside of the classroom, it also includes a chapter on copyright and fair use.

From interviews with librarians, instructional technology experts and specialists, the book includes background information to help educators sort through the maze of Internet sites and resources. Even more, there are ready-to-use handouts and activities for students.

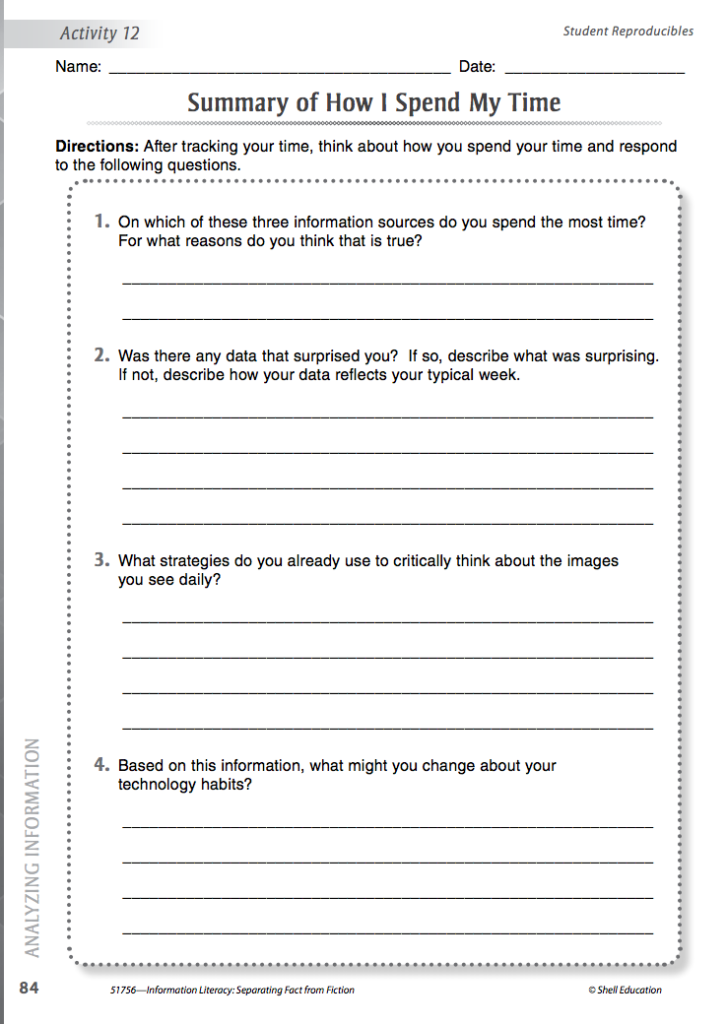

If you teach expository or opinion writing, Information Literacy would be a valuable resource for your classroom and professional development. Here’s a sample page to give you an idea of what’s inside:

Should you read Information Literacy: Separating Fact from Fiction, please let me know your thoughts! I hope you enjoy it! It’s available now on Amazon! Or, you can purchase it at your favorite bookstore!

If you’re looking for last-minute gifts for a middle schooler, you might want to check out Just One Thing! by Nancy Viau. And… you can get discussion questions for FREE!

If you’re looking for last-minute gifts for a middle schooler, you might want to check out Just One Thing! by Nancy Viau. And… you can get discussion questions for FREE!

From the back cover: Anthony Pantaloni needs to figure out one thing he does well–one thing that will replace the Antsy Pants nickname he got tagged with on the first day of fifth grade, and something he can “own” before moving up to middle school next year. It seems that every kid in Carpenter Elementary has some claim to fame: Marcus is Mr. Athletic, Alexis is Smart Aleck, Bethany has her horse obsession, and even Cory is known as the toughest kid in the school. Ant tries lots of things, but nothing sticks! IT doesn’t help that there are obstacles along the way–a baton-twirling teacher, an annoying cousin, and Dad’s new girlfriend, to name a few. Just One Thing! is chock full of hilarious adventures that will keep young readers cheering for Ant until the very end. For ages 8-12.

Take a look! Nancy and I had so much fun creating the discussion questions for you, too! We hope you enjoy them.

I’m participating in #kidlitforAleppo on Twitter through Wednesday, Dec. 21, 2016. If you make a donation to an organization helping in Aleppo, post an image of your receipt (mark out the identifying details or take a screenshot of any part of the e-receipt that doesn’t show your personal information) to my Tweet here. I will randomly choose a winner on Dec. 22.

For a background on #kidlitforAleppo, or to see what organizations qualify, read Dana Alison Levy’s post, “The Stories We Don’t Want to Tell: Aleppo.” (Note: Dana Alison Levy and Rachel Allen came up with the idea!)

While the Common Core may be controversial in the education world, it is good news for kid lit writers. Since the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) list things kids should know and be able to do at each grade level, they help authors align their books with what kids are learning, and they also enable authors to have valuable discussions with teachers who use their books. In order to accomplish these professional endeavors, it is important for authors to understand how the CCSS came into being, how to read the standards, and how to posit books within the Common Core context.

While the Common Core may be controversial in the education world, it is good news for kid lit writers. Since the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) list things kids should know and be able to do at each grade level, they help authors align their books with what kids are learning, and they also enable authors to have valuable discussions with teachers who use their books. In order to accomplish these professional endeavors, it is important for authors to understand how the CCSS came into being, how to read the standards, and how to posit books within the Common Core context.

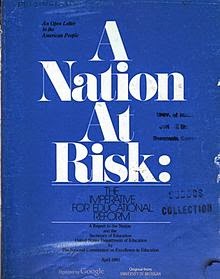

In 1983, a scathing report called “A Nation at Risk” came out that lambasted the American education system. The report cited that educational issues such as high teacher turnover rates, declining test scores, and high rates of illiteracy among adults were threatening the United State’s ability to compete with other industrialized nations. The report drove education to the forefront of politics, and calls for sweeping reforms were made to improve teaching, teacher education, and education standards.

In 1983, a scathing report called “A Nation at Risk” came out that lambasted the American education system. The report cited that educational issues such as high teacher turnover rates, declining test scores, and high rates of illiteracy among adults were threatening the United State’s ability to compete with other industrialized nations. The report drove education to the forefront of politics, and calls for sweeping reforms were made to improve teaching, teacher education, and education standards.

Because education policy is set at the state level, states began to develop their own standards for addressing academic achievement. And, in 2002, George W. Bush signed “No Child Left Behind” (NCLB) into law. The goal of NCLB was to raise the level of education for all American children, and it required districts to test students every year in 3rd-8th grade on reading and math and to report their progress.

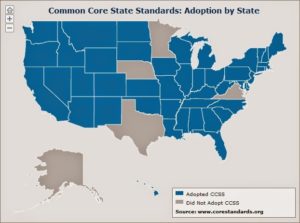

Since every state had its own standards and tests to measure student achievement, there were obvious difficulties in comparing the data across the country. So, in 2009-2010, a council of state governors and state heads of education worked to develop internationally bench-marked standards that they hoped would be adopted and used by every state. At the time of this post, forty-five states have adopted the Common Core State Standards (Alaska, Minnesota, Nebraska, Texas, and Virginia have not).

The Common Core does not identify how teachers should teach, nor does it limit or state all that can and should be taught. Rather, it’s a list of things students should know and be able to do at each grade level in English Language Arts (ELA) and in math.

The Common Core does not identify how teachers should teach, nor does it limit or state all that can and should be taught. Rather, it’s a list of things students should know and be able to do at each grade level in English Language Arts (ELA) and in math.

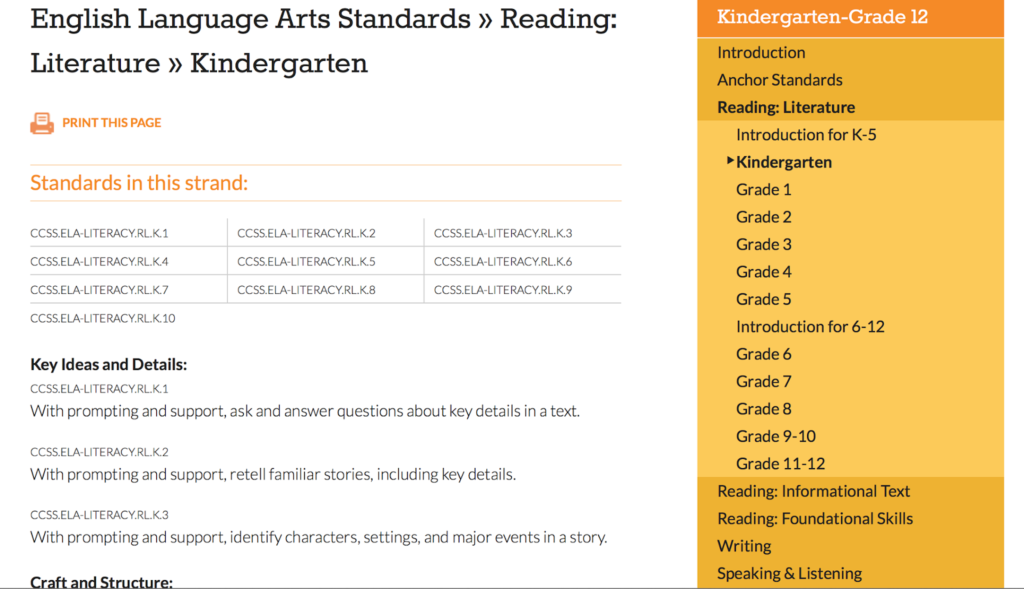

Since this post is for authors, I’ll focus solely on the ELA standards, but if you’d like to visit the math standards, the same logic applies. Go here to view the actual ELA standards. Once there, you will see that the standards are broken down in the following manner according to grade level. If you click on one of the ELA strands by grade, a list of standards appears, broken down by subtopic:

For example, in the Reading: Literature strand for Kindergarten, RL.K.1 is the first standard. It states that students should “With prompting and support, ask and answer questions about key details in a text.” The first letter(s) identify the type of standard from the list above (RL in the example=Reading for Literature). The second piece is the grade level (K in the example is Kindergarten). And the final number represents the number of standard (1 in the example means it’s the first of ten standards in the Reading for Literature standards).

Each grade has its own standards, but there are some general pieces of information to note. First, in reading instruction there should be a balance of literature and informational texts. In writing, there is an emphasis on argument and informative/explanatory. Students will also be required to write about sources and to develop high level thinking/problem solving skills at an early age. Even kindergartners will be expected to write narrative, argumentative, and informative pieces. For speaking and listening, both formal and informal speech are required. And with language, students will be required to use and understand both general academic (such as ‘observe’) and domain-specific vocabulary (such as ‘cells’).

Authors who are knowledgeable about the Common Core can have mutually beneficial conversations with teachers about their books. Knowing the six strands of ELA standards is a great start. If you’ve written a picture book, chances are you can create lesson activities to meet the Reading for Literature (RL) standards. If you’ve written a nonfiction book, chances are you can create lesson activities to meet the Reading for Informational Text (RI) standards. Should you be lucky enough to go into a classroom, you can use the specific grade-level standards. But, if you’ve written a book and want to be more open-ended, you can refer to the ELA College and Career Readiness Anchor Standards. These are the more general, overarching standards (as apposed to the additional specificity of grade-specific standards. Together the anchor standards and the grade level standards define the skills and understandings that all students must demonstrate by the time of graduation). You can find these anchor standards on the Common Core website.

For example, the first anchor standard for Reading is Literacy.CCRA.R.1 – Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusion drawn from the text.

Just as before, the breakdown is the same: CCRA=College and Career Readiness Anchor standard, R=Reading, 1=first standard.

All this information provided by the Common Core means that writers have the tools on hand to market their books to educators and students. It means authors have the tools to create activities and guides to help teachers use their books in classrooms in a meaningful way. It means authors have the tools to connect with the education world. And that’s very good news, indeed.

Sources:

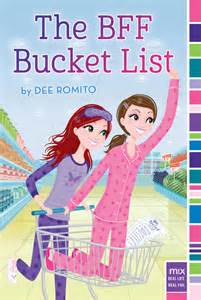

Follow the links below to get a FREE teacher’s guide and discussion questions for Dee Romito’s The BFF Bucket List.

Follow the links below to get a FREE teacher’s guide and discussion questions for Dee Romito’s The BFF Bucket List.

Summary: Ella and Skyler have been best friends since kindergarten–so close that people smoosh their names together like they’re the same person: EllaandSkyler. SkylerandElla.

But Ella notices the little ways she and Skyler have been slowly drifting apart. And she’s determined to fix things with a fun project she’s sure will bring them closer together—The BFF Bucket List. Skyler is totally on board.

The girls must complete each task on the list together: things like facing their fears, hosting a fancy dinner party, and the biggest of them all—speaking actual words to their respective crushes before the end of summer. But as new friends, epic opportunities, and super-cute boys enter the picture, the challenges on the list aren’t the only ones they face.

And with each girl hiding a big secret that could threaten their entire friendship, will the list–and their BFF status–go bust?

Themes of friendship, challenges, and growing up are woven throughout the book.

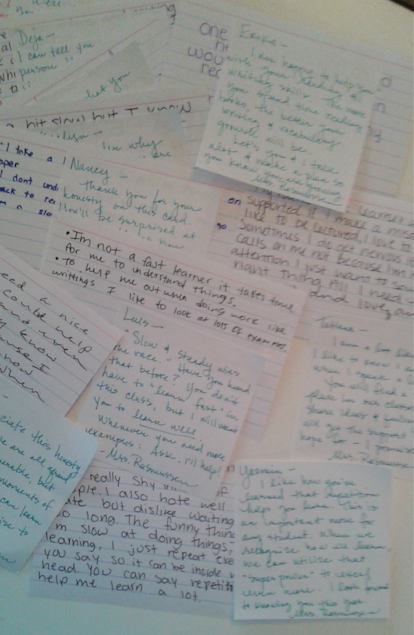

A friend passed along this post about engaging students with sticky-note conversations. It’s a clever and quick idea to try in the classroom; it builds trust and writing into the routine in an authentic and meaningful way. Take a look!

A friend passed along this post about engaging students with sticky-note conversations. It’s a clever and quick idea to try in the classroom; it builds trust and writing into the routine in an authentic and meaningful way. Take a look!

For authors, I can envision using this technique for school visits or ways to engage in conversation about your books within classroom instruction.

While the most effective element was explicitly teaching students writing strategies, it is important to note that all of these elements proved effective, and can be combined to strengthen adolescent literacy development. It is also important to note that many of the effect sizes differed only minimally, so we need to be cautious in interpreting the differences in effect.

What surprised me most was the rank of the study of models (#10). I keep reading about mentor texts. In fact, I contributed two blog entries about their benefits here and here. And, it’s true that they’re helpful in teaching students to write well. But, mentor texts are only helpful if students have the basic writing skills beforehand in order to learn from masters and extrapolate that information into their own work, and when we use them in conjunction within a larger literacy and writing framework.

The report repeatedly mentioned that these elements do not make up a complete writing curriculum on their own. This made me wonder: what does constitute a solid writing curriculum for fourth grade and up? And, what are some additional practices in writing instruction? I’m familiar with the writing process, Writer’s Workshop, 6 +1 traits, and others. But, what else is there? And how do they all tie together with reading, listening, speaking, viewing, and visually representing? And, why is reading still receiving more attention than writing? Obviously, I have some more reading and thinking to do!

A good study should shed light on questions while at the same time inciting more. I’ve only summarized a portion of this report–I did not mention the history of writing instruction, the necessity of writing or the consequences of poor writing, additional methodologies to consider, and more. Click here to read the full report.

In the meantime, do you have a reaction to the findings or my questions? If so, please share your thoughts!

If students are to make knowledge their own, they must struggle with the details, wrestle with the facts, and reword raw information and dimly understood concepts into language they can communicate to someone else. In short, if students are to learn, they must write.”

–the National Commission on Writing, as cited in Writing Next

A FREE teacher guide is now available for Tricky Vic, by Greg Pizzoli!

In the early 1900s, Robert Miller, aka “Tricky Vic,” conned his way through Europe to America and back again. He swindled unsuspecting marks into giving him thousands of dollars for a money-printing box that did not actually print counterfeit money, stole from wealthy passengers on transatlantic steamships, and conned scrap metal dealers into bidding for the rights to dismantle the Eiffel Tower before being arrested in New York for a counterfeiting scheme. These thrilling and daring exploits provide insights into one of the world’s greatest con artists, and show readers how a con man lives and operates. Informational sidebars and back matter provide background for the time period and help kids understand this narrative picture book biography.

Click here to download the guide for Tricky Vic, which I created in conjunction with the author. There’s plenty to think about and discuss with this excellent book. We hope you enjoy it!

The newest teachers’ guide is now available!

The newest teachers’ guide is now available!

No Sleep for the Sheep! is a fun, rollicking romp about a sheep who just wants to sleep. But, animal after animal keeps interrupting ’til morning.

Click here to preview or order your guide for this adorable picture book by Karen Beaumont and Jackie Urbanovic.