While the Common Core may be controversial in the education world, it is good news for kid lit writers. Since the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) list things kids should know and be able to do at each grade level, they help authors align their books with what kids are learning, and they also enable authors to have valuable discussions with teachers who use their books. In order to accomplish these professional endeavors, it is important for authors to understand how the CCSS came into being, how to read the standards, and how to posit books within the Common Core context.

While the Common Core may be controversial in the education world, it is good news for kid lit writers. Since the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) list things kids should know and be able to do at each grade level, they help authors align their books with what kids are learning, and they also enable authors to have valuable discussions with teachers who use their books. In order to accomplish these professional endeavors, it is important for authors to understand how the CCSS came into being, how to read the standards, and how to posit books within the Common Core context.

A Very Brief History of Education Reform and the Common Core

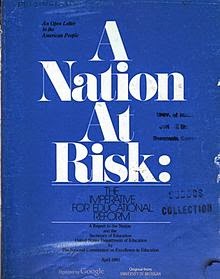

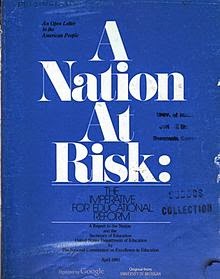

In 1983, a scathing report called “A Nation at Risk” came out that lambasted the American education system. The report cited that educational issues such as high teacher turnover rates, declining test scores, and high rates of illiteracy among adults were threatening the United State’s ability to compete with other industrialized nations. The report drove education to the forefront of politics, and calls for sweeping reforms were made to improve teaching, teacher education, and education standards.

In 1983, a scathing report called “A Nation at Risk” came out that lambasted the American education system. The report cited that educational issues such as high teacher turnover rates, declining test scores, and high rates of illiteracy among adults were threatening the United State’s ability to compete with other industrialized nations. The report drove education to the forefront of politics, and calls for sweeping reforms were made to improve teaching, teacher education, and education standards.

Because education policy is set at the state level, states began to develop their own standards for addressing academic achievement. And, in 2002, George W. Bush signed “No Child Left Behind” (NCLB) into law. The goal of NCLB was to raise the level of education for all American children, and it required districts to test students every year in 3rd-8th grade on reading and math and to report their progress.

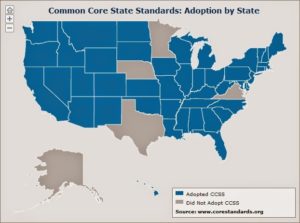

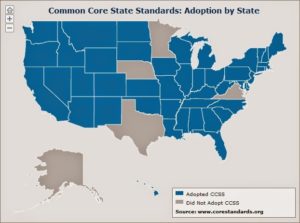

Since every state had its own standards and tests to measure student achievement, there were obvious difficulties in comparing the data across the country. So, in 2009-2010, a council of state governors and state heads of education worked to develop internationally bench-marked standards that they hoped would be adopted and used by every state. At the time of this post, forty-five states have adopted the Common Core State Standards (Alaska, Minnesota, Nebraska, Texas, and Virginia have not).

What Does the Common Core Say?

The Common Core does not identify how teachers should teach, nor does it limit or state all that can and should be taught. Rather, it’s a list of things students should know and be able to do at each grade level in English Language Arts (ELA) and in math.

The Common Core does not identify how teachers should teach, nor does it limit or state all that can and should be taught. Rather, it’s a list of things students should know and be able to do at each grade level in English Language Arts (ELA) and in math.

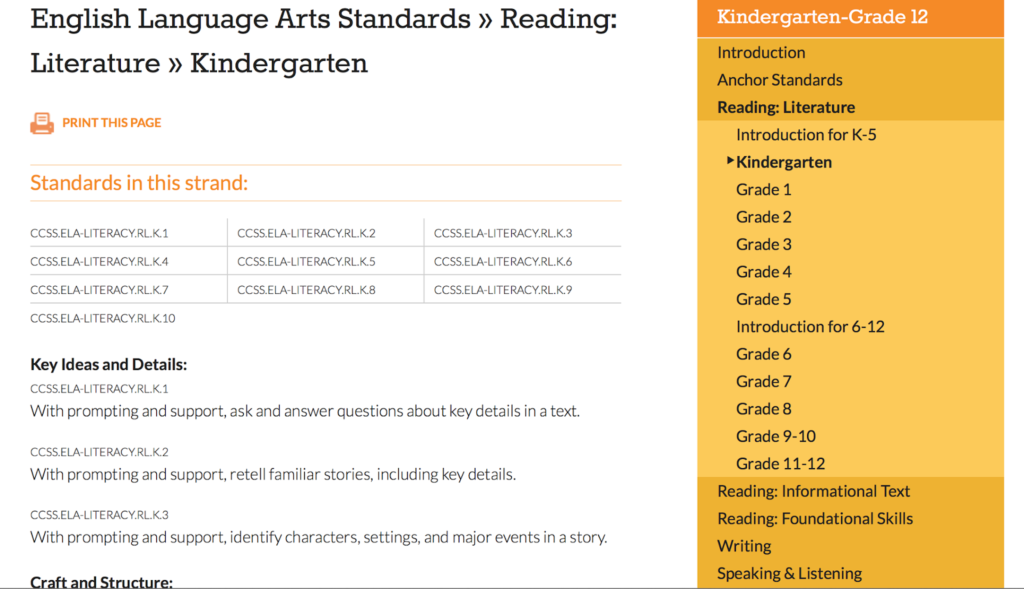

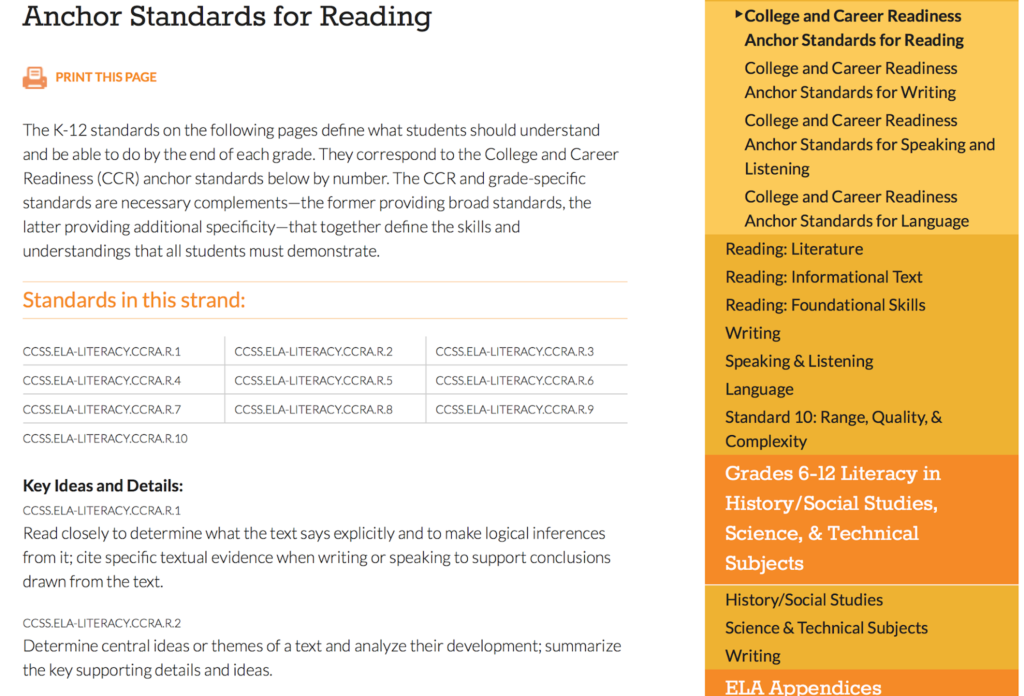

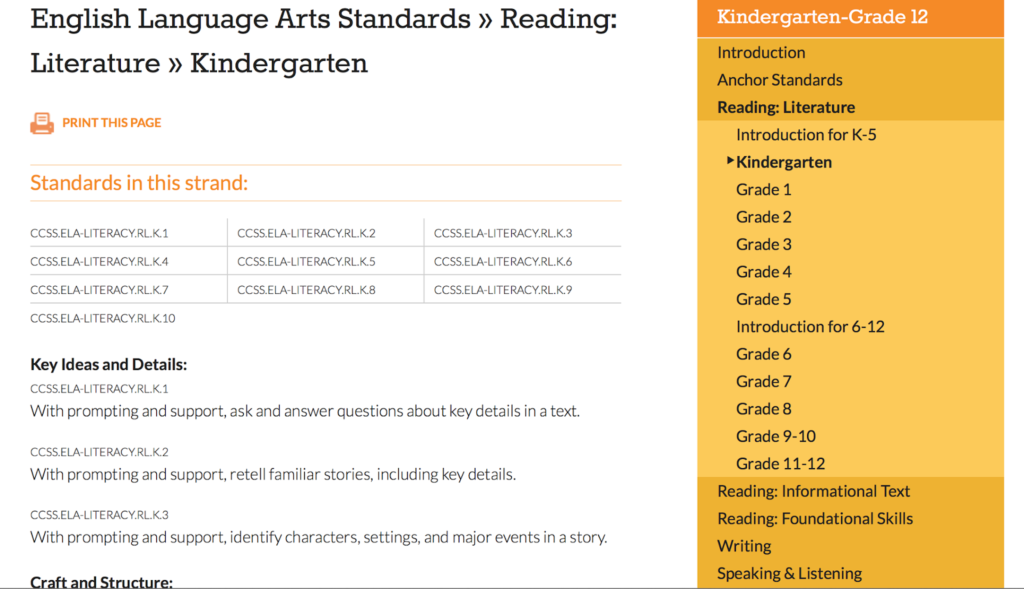

Since this post is for authors, I’ll focus solely on the ELA standards, but if you’d like to visit the math standards, the same logic applies. Go here to view the actual ELA standards. Once there, you will see that the standards are broken down in the following manner according to grade level. If you click on one of the ELA strands by grade, a list of standards appears, broken down by subtopic:

For example, in the Reading: Literature strand for Kindergarten, RL.K.1 is the first standard. It states that students should “With prompting and support, ask and answer questions about key details in a text.” The first letter(s) identify the type of standard from the list above (RL in the example=Reading for Literature). The second piece is the grade level (K in the example is Kindergarten). And the final number represents the number of standard (1 in the example means it’s the first of ten standards in the Reading for Literature standards).

Each grade has its own standards, but there are some general pieces of information to note. First, in reading instruction there should be a balance of literature and informational texts. In writing, there is an emphasis on argument and informative/explanatory. Students will also be required to write about sources and to develop high level thinking/problem solving skills at an early age. Even kindergartners will be expected to write narrative, argumentative, and informative pieces. For speaking and listening, both formal and informal speech are required. And with language, students will be required to use and understand both general academic (such as ‘observe’) and domain-specific vocabulary (such as ‘cells’).

How Can Authors Use the Common Core to Promote Their Books?

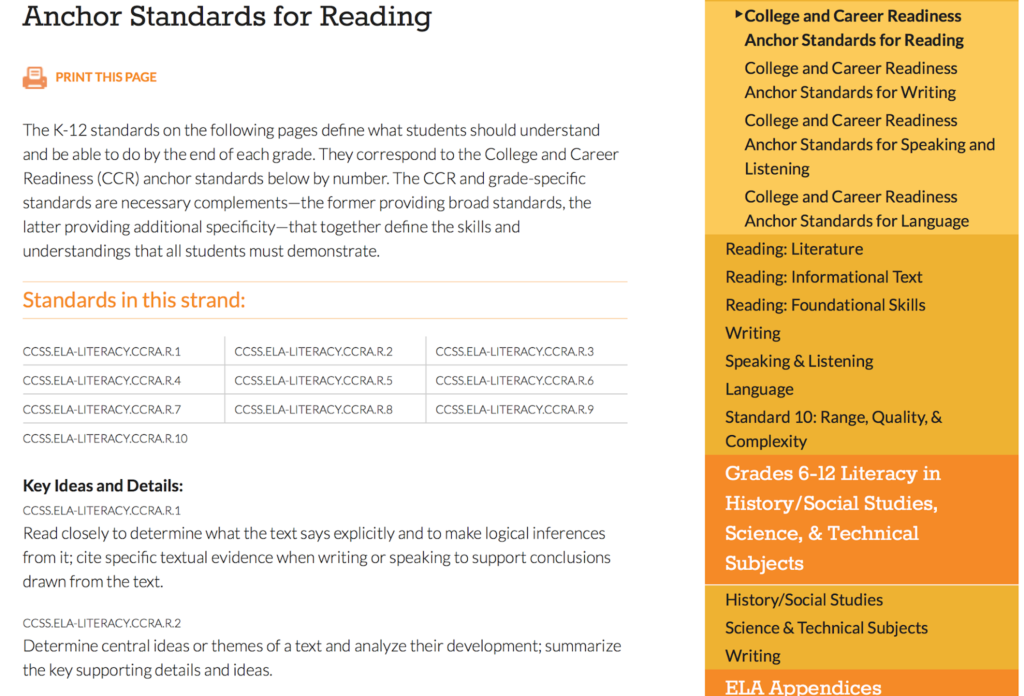

Authors who are knowledgeable about the Common Core can have mutually beneficial conversations with teachers about their books. Knowing the six strands of ELA standards is a great start. If you’ve written a picture book, chances are you can create lesson activities to meet the Reading for Literature (RL) standards. If you’ve written a nonfiction book, chances are you can create lesson activities to meet the Reading for Informational Text (RI) standards. Should you be lucky enough to go into a classroom, you can use the specific grade-level standards. But, if you’ve written a book and want to be more open-ended, you can refer to the ELA College and Career Readiness Anchor Standards. These are the more general, overarching standards (as apposed to the additional specificity of grade-specific standards. Together the anchor standards and the grade level standards define the skills and understandings that all students must demonstrate by the time of graduation). You can find these anchor standards on the Common Core website.

For example, the first anchor standard for Reading is Literacy.CCRA.R.1 – Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusion drawn from the text.

Just as before, the breakdown is the same: CCRA=College and Career Readiness Anchor standard, R=Reading, 1=first standard.

All this information provided by the Common Core means that writers have the tools on hand to market their books to educators and students. It means authors have the tools to create activities and guides to help teachers use their books in classrooms in a meaningful way. It means authors have the tools to connect with the education world. And that’s very good news, indeed.

Sources:

- Bidwell, Allie. “The History of Common Core State Standards.” US News. U.S.News & World Report, 27 Feb. 2014. Web. 25 Nov. 2014.

- Graham, Edward. “‘A Nation at Risk’ Turns 30: Where Did It Take Us? – NEA Today.” NEA Today. N.p., 25 Apr. 2013. Web. 26 Nov. 2014.

- Meador, Derrick. “An In-Depth Look at the Common Core.” About Education. N.p., n.d. Web. 26 Nov. 2014.

- “A Nation At Risk.” Archived:. N.p., Apr. 1983. Web. 26 Nov. 2014. <https://www2.ed.gov/pubs/NatAtRisk/risk.html>.

- Nelson, Libby. “What Is the Common Core?” Vox. N.p., 7 Oct. 2014. Web. 26 Nov. 2014.

- Scherer, Melissa. “A NATION AT RISK: THE IMPERATIVE FOR EDUCATIONAL REFORM, 1983.” N.p., n.d. Web. 26 Nov. 2014. <https://www3.nd.edu/~rbarger/www7/nationrs.html>.

While the Common Core may be controversial in the education world, it is good news for kid lit writers. Since the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) list things kids should know and be able to do at each grade level, they help authors align their books with what kids are learning, and they also enable authors to have valuable discussions with teachers who use their books. In order to accomplish these professional endeavors, it is important for authors to understand how the CCSS came into being, how to read the standards, and how to posit books within the Common Core context.

While the Common Core may be controversial in the education world, it is good news for kid lit writers. Since the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) list things kids should know and be able to do at each grade level, they help authors align their books with what kids are learning, and they also enable authors to have valuable discussions with teachers who use their books. In order to accomplish these professional endeavors, it is important for authors to understand how the CCSS came into being, how to read the standards, and how to posit books within the Common Core context. In 1983, a scathing report called “A Nation at Risk” came out that lambasted the American education system. The report cited that educational issues such as high teacher turnover rates, declining test scores, and high rates of illiteracy among adults were threatening the United State’s ability to compete with other industrialized nations. The report drove education to the forefront of politics, and calls for sweeping reforms were made to improve teaching, teacher education, and education standards.

In 1983, a scathing report called “A Nation at Risk” came out that lambasted the American education system. The report cited that educational issues such as high teacher turnover rates, declining test scores, and high rates of illiteracy among adults were threatening the United State’s ability to compete with other industrialized nations. The report drove education to the forefront of politics, and calls for sweeping reforms were made to improve teaching, teacher education, and education standards.

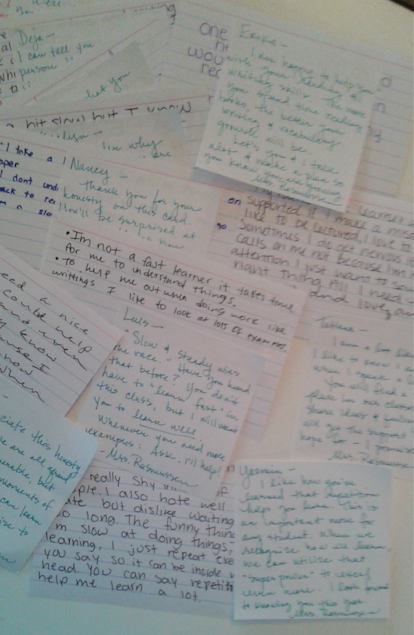

A friend passed along

A friend passed along